What do we mean by digital literacy?

Key findings: The digital literacy, digital technologies skills and techniques currently being taughtFind out what we mean by digital literacy.

When asked in the focus groups what participants understood by the term ‘digital literacy’ it was predominantly defined in terms of what training is available to increase digital literacy, digital skills, and digital competence.

Quote

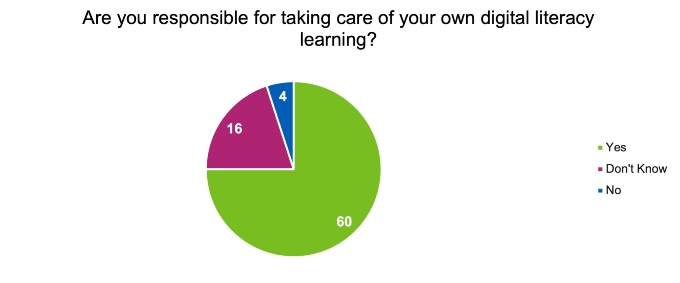

One participant noted that there is a lack of clarity across health and care professions about what digital literacy is. It appears that as a result of this, many students are not provided any digital training and they feel much of their digital literacy is self-taught. Many students feel they are responsible for taking care of their own digital literacy (Figure 14).

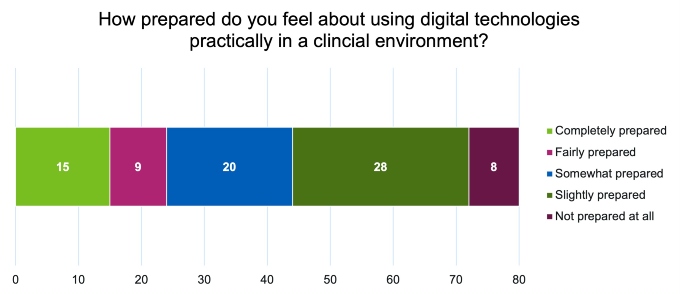

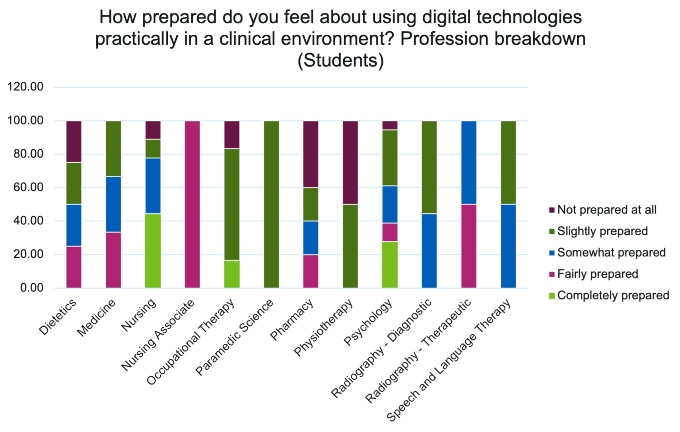

As a result, many students reported only feeling slightly prepared or somewhat prepared to use digital technologies in a clinical environment (Figure 15), and when broken down by profession, physiotherapy and pharmacy students were more likely to report feeling not prepared at all (Figure 16). Nursing students were the group most likely to report feeling completely prepared (Figure 16).

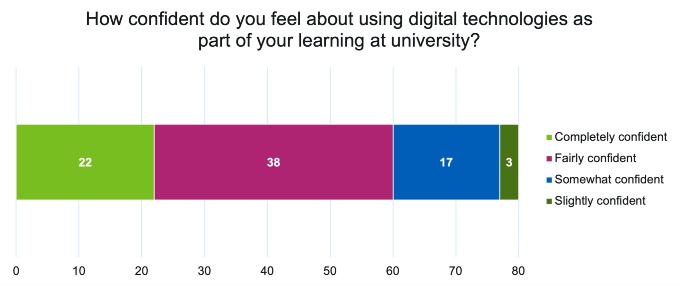

When students were asked how confident they felt about using digital technologies as part of learning at university, most students reported feeling fairly confident (Figure 17). This suggests that whilst students do not feel prepared for using digital technologies on placement, they feel more confident about using digital technologies in a university environment.

Therefore, there is an argument for exploring a broad range of digital technologies in a university environment to allow students to use them in a safe setting where they feel confident, and in turn, this will prepare them for using these technologies in a clinical environment. Also, this may indicate an underuse of digital technologies in practice due to poor digital literacy capabilities

Page last reviewed: 10 May 2023

Next review due: 10 May 2024