4.2 Specialist artificial intelligence (AI) skills within the NHS

Chapter 4: Workforce TransformationThis research suggests that many healthcare settings have gaps in relation to skills and capabilities.

As noted in section 1.1, specialist skills and roles that relate to the Creator and Embedder archetypes can be described differently across entities, initiatives and research reports. These include: ‘digital, data and technology (DDaT) specialists’, ‘data scientists’, ‘data analysts’, ‘data engineers’, ‘clinical scientists’, ‘clinical informaticians’, ‘clinical bioinformaticians’, ‘digital professionals’, and ‘AI professionals’. This variance highlights the need for further work to reach consensus on the terminology and clarify links across these roles.

Feedback from the interviews conducted for this research suggests that many healthcare settings have significant gaps in relation to the skills and capabilities associated with the Creator and Embedder archetypes.

Aspects of developing and deploying artificial intelligence (AI) technologies may require increased workload when collecting, managing and processing data. The NHS may need to employ and train professionals to ensure appropriate resourcing or address any resource gaps, including the projected need for 11,953 more clinical informatics professionals by 2030 outlined in HEE’s ‘Data driven healthcare in 2030’ report. The report recommends a ‘focus on the supply factors affecting the NHS digital technology and informatics workforce and developing an action plan to address the need for an increase in staffing levels’. The report highlights that 'the level of investments required in developing a specialised AI workforce will be significant, and the NHS will face recruitment and retention challenges in a competitive labour market’.7

Interviewees for this research observed that, given the current gap, capabilities associated with the Creator and Embedder archetypes are provided through collaborative projects with industry innovators or academia. This suggests that, in the short term, specialist technical roles like data scientists and AI engineers may need to be recruited or contracted from outside the NHS. To do so, healthcare settings will need to compete with industry for technically skilled staff, and build environments that enable these individuals to apply their expertise rapidly and with real-world impact on patient care.

Interviewees also noted that the adoption of some AI technologies may lead to re-deployment of existing resources, either as a result of automating human tasks or by shifting volumes of work to different parts of service delivery models. Due to these changes, some professionals may require new data science skills. This will need to be supported and planned due to significant perceived challenges, especially for smaller healthcare settings.

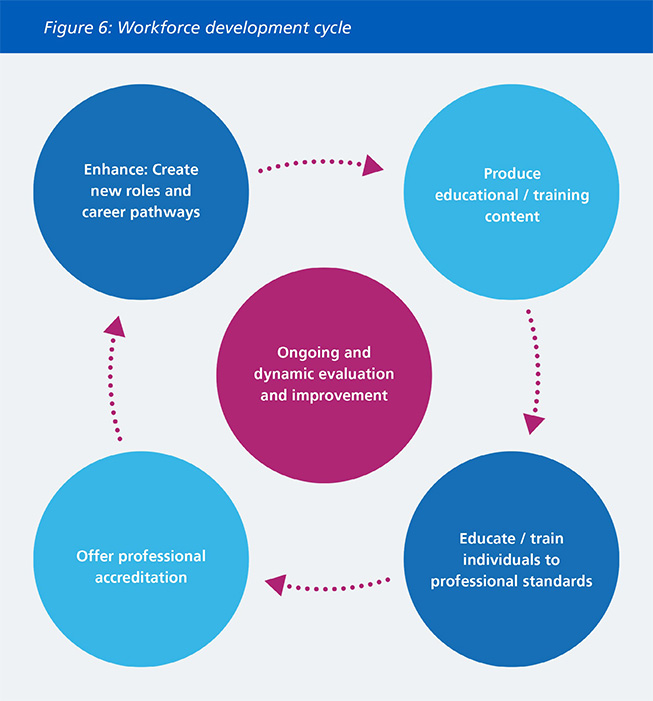

In the long term, developing and sustaining specialists AI skills will require development of appropriate education, accreditation and career pathways as illustrated in Figure 6, and discussed in the following subsections. This should be supported by constant and dynamic evaluation and improvement of educational efforts, professional accreditation routes and career pathways.

The ‘Data saves lives’ strategy outlines existing efforts to build analytical and data science capabilities, including building the profile of data and analysis as a profession through competency frameworks, networks, training, career opportunities and status, and work with the Developing Data and Analysis as a Profession Board.11

4.2.1 Training and professionalisation of specialist AI skills

Training for clinical informatics roles (associated with Embedder and Creator archetypes)

Developing Creator and Embedder capabilities within the NHS will require establishing new training pathways and expanding existing training programmes for new specialist roles and positions (such as clinical scientists). The aim would be to develop specialists with both clinical and AI-related expertise.

A few training programmes for individuals with specialist skills required to undertake Embedder and Creator roles currently exist within the NHS but have limited training numbers. For example, the Scientist Training Programme (STP) by the National School of Healthcare Science (NSHS), is a 3-year programme of work-based learning, supported by a university accredited master's degree that covers roles for informatics in healthcare science, including Clinical Bioinformatics Genomics, Clinical Informatics (formerly known as Bioinformatics Health Informatics) and Clinical Scientific Computing (formerly known as Bioinformatics Physical Science).21

In 2021, there were only 6 training posts available for informatics roles in genomics, 7 in health informatics, and 4 in physical sciences (the sub-specialisms relevant to the AI Embedder archetype).22 Training programme numbers will need to be significantly expanded to meet the forecasted need for clinical informatics professionals if this cohort is expected to support adopting AI technologies at scale.

Upskilling

It may also be appropriate to upskill and retrain existing professionals with clinical informatics skills to move into new job roles. Further to the STP, the Academy for Healthcare Science (AHCS), a joint initiative of the UK Health Departments and the professional bodies across Healthcare Science, provides an equivalence route for existing NHS staff to acquire the title of clinical informatician through apprenticeships in NHS trusts or training by non-NHS organisations.23 Further training routes that allow for transfer of skills from outside the NHS could also be considered. Interviewees for this research noted that transferring skills should be facilitative rather than restrictive, supported with pathways to obtain the required competencies rather than relying on onerous paperwork to prove skills.

Digital and AI specialist clinicians

AI multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) will require clinicians with advanced AI knowledge, and both clinical and technical expertise. These individuals will need to be able to communicate effectively with technical specialists like data scientists, liaise with clinical teams, promote safety and ensure products deliver real clinical impact.

Clear job roles and career pathways should be established for digital and AI specialist clinicians. HEE’s ‘Data driven healthcare in 2030’ report recommends ‘developing standardised job roles for multi-professional clinicians, including clinician informaticians, to address the workforce demand anticipated across the depth and breadth of clinical informatics’.7

Interviewees for this research reported that at present, clinicians can develop skills and knowledge related to digital health, data science and AI only by pursuing self-directed, voluntary learning in their own time or taking time out of training to complete additional qualifications or work for industry organisations outside the NHS in order to gain skills and experience. They reported that digital and data-related topics are generally not included in undergraduate or postgraduate curricula, and are often not supported through study budgets or protected time.

Clinicians at all stages of their career should actively be encouraged to develop skills in Digital, Data and Technology (DDaT), particularly data and informatics skills, including AI. This could be accomplished through inclusion of digital topics in undergraduate and postgraduate curricula, by offering protected time and funding for digital skills training throughout the clinical workforce and by creating joint digital and clinical training programmes that combine clinical work with roles within AI MDTs and/or placements in academia or industry.

Health Education England (HEE) has partnered with the University of Manchester to develop a ‘Clinical Data Science’ programme due for launch in September 2023, which aims to increase clinician awareness of data science accredited with a postgraduate certificate. Similar education material could be considered for AI, and made accessible to a wider range of clinicians across the NHS.

Funded by HEE, the London Medical Imaging and AI Centre for Value Based Healthcare has launched fellowships in clinical AI.24 The year-long fellowship programme offers trainees the chance to develop AI-related skills for 2 days a week (or 40 per cent time equivalent) alongside less than full-time training. The fellows undertake a programme of teaching aligned with the Clinical AI Curriculum developed by Guy's and St Thomas' Department of Medical Physics whilst also contributing to immersive AI projects in live hospital workflows, supervised by experts in clinical AI.

Flexible portfolio training (FPT) is a pilot initiative within higher specialty training offered by HEE and the Royal College of Physicians that protects one day a week (or 20 per cent time equivalent) for professional development without impact on the length of training.25 Clinical informatics is one of 4 pathways offered within FPT. Trainees on the clinical informatics pathway develop capabilities in information governance and security, system use and clinician safety, digital communication assessment, information and knowledge management, patient empowerment and emerging technologies.

Collaborative training with academia and industry

Interviewees for this research noted the importance of collaboration between healthcare settings, academia and industry innovators to train and employ individuals with Embedder and Creator skills.

HEE’s ‘The future of clinical bioinformaticians in the NHS’ report recommended to ‘set out a proposed model of how to involve external partners in the commissioning and training of clinical bioinformaticians by looking at research departments’.8 Reciprocal fellowship placements with industry are being considered as part of the Clinical Scientist Training Programme (STP) programme.

HEE has set up an industry roundtable and is exploring the potential for collaborative training opportunities with industry innovators, including members of the Association of British HealthTech Industries, the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry, Tech UK, Health Tech Alliance, Imagine Talent and the Organisation for the Review of Care and Health Applications. As an example, the Imagine talent collaborative community explores the future of talent for a digital age and are trialling a digital talent model.26 This involves giving an opportunity to data scientists from various organisations (including at NHS and HEE) to work across sectors and organisations to build their expertise and experience.

HEE has also established the Health Innovation Placement (HIP) pilot27 as part of the Digital Readiness Education Programme.28 It provides leaders with an opportunity to develop through exposure with start-ups/small-medium organisations (SMEs) and to work on the development of a technological solution to a specific NHS problem.

Informatics Skills Development Networks (ISDNs)

HEE has supported the creation of eight regional ISDNs across England, which are based on the existing Finance and Procurement Skills Development Networks models.29 The ISDNs aim to support the training and career development of digital professionals at a regional level by providing educational programmes, networking opportunities and acting as an interface with key professional bodies including the Faculty of Clinical Informatics (FCI), British Computer Society (BCS), College of Healthcare Information Management Executives (CHIME), Federation of Informatics Professionals (FEDIP) and Association of professional healthcare Analysts (AphA).

ISDNs could play a role in co-ordinating key components of Figure 6’s workforce development cycle, including the delivery of education, accreditation with professional bodies and guiding the creation of appropriate job roles and career pathways within the region.

Professionalisation and accreditation

Professionalisation of the DDaT data family and clinical informatics workforce, overseen by a recognised governing body, would support the development and recognition of these roles. This could include formal qualifications such as post-graduate certificates, diplomas, and degrees, alongside more flexible educational pathways, competency frameworks and the creation of recognised job roles.

Current related initiatives include the NHSE Digital Workforce Programme within the System CIO/Director of Levelling-up Directorate, and the development and testing of a National Competency Framework for Data Professionals in Health and Care that will include a set of core competencies for health and care data professionals.42

Several organisations have been supporting broader work in the professionalisation of the data and informatics workforce including the Faculty of Clinical Informatics (FIC), Federation for Informatics Professionals (FEDIP) and Association of Professional Healthcare Analysts (AphA). Cross-government initiatives like the Digital, Data and Technology (DDaT) Profession Capability Framework30 can inform approaches in healthcare.

4.2.2 Rewarding and retaining individuals with specialist skills

HEE’s ‘The future of clinical bioinformaticians in the NHS’ notes that retention of this cohort has been challenging, despite the small numbers of clinical bioinformaticians trained each year and growing demand for their skills within the NHS.8 The major factors affecting the retention and utilisation of clinical bioinformaticians include having to continuously deal with undemanding and conventional tasks, combined with a perceived lack of promotion opportunities. As the report suggests ‘The NHS clinical bioinformaticians want to stay only if they can do the work that they are trained for.’ 8

The current levels of renumeration for specialist skills within healthcare settings may be limiting external interest in these roles. Data scientists and data analysts in the private sector who are proficient in machine learning and AI can expect to earn more than twice the salary of NHS analyst roles.4 The Agenda for Change pay scale framework31 currently limits the salaries of data science professionals as they are classified as ‘administrative/clerical’ staff. As suggested in the ‘Data driven healthcare in 2030’ report ‘the financial reward structures for the NHS digital technology and health informatics workforce will need to be reviewed with particular attention given to the competitiveness of the labour market in affecting recruitment and retention of staff in the NHS’.7 This was re-iterated in the Goldacre Review, stating that ‘the NHS must stop expecting to pay highly skilled technical staff in data science and software development on salary scales devised for low and intermediate level IT technical support.’ It recommended the implementation of ‘competitive remuneration packages’ for technical skills that ‘reflects market value’.4

Remuneration may not be the most important consideration to attract and retain individuals with specialist skills. Perhaps surprisingly, ‘The future of clinical bioinformaticians in the NHS’ report notes that ‘income had not been an essential factor for the career choices of the NHS clinical bioinformaticians’. The report suggests that clinician bioinformaticians find current wages acceptable and appreciate the additional benefits, such as the NHS pension, holiday entitlement, and maternity/paternity leave. Amongst the bioinformaticians who had left the NHS, most did not cite income as being a factor in changing jobs.8

The report also notes that, currently, there are few individuals with clinical bioinformatics skills in relatively senior roles. Consequently, these roles are not well represented in senior decision-making processes, which may have been preventing clinical bioinformaticians from effectively conveying their needs to the management of their trusts.8

These insights suggest that other factors affecting retention like opportunities for professional development, and recognition of the value of clinical bioinformaticians at a senior level are important and need to be considered.

4.2.3 Digital Leadership Roles

Interviewees for this research noted that some health settings have already created senior roles to oversee the deployment of AI technologies. An example is the role of Clinical Informatics Lead responsible for providing and leading development of AI knowledge and skills, including acting as a mentor for other senior leaders, and overseeing implementation of AI technologies across their institution, with assistance from clinical leads at each unit.

Other specialist senior clinical informatics roles within the NHS include Chief Clinical Information Officers (CCIO) and Chief Nursing Information Officers (CNIO). There have been some developments in setting standards for these roles; for example, the Faculty of Clinical informatics have published a model job description for Chief Clinical Informatics Officers (CCIOs) 32 and regional Informatics Skills Development Networks (ISDNs) have set up CCIO special interest groups (SIGs). However, further professionalisation of these roles should be considered, including the creation of joint clinical digital training pathways with protected time spent in digital roles. This should be accompanied by clear career trajectories with support in achieving a specific set of competencies required for digital clinical leadership positions.

The ‘Data driven healthcare in 2030’ report sketches a new cadre of professional digital leaders to drive forward the adoption of AI and data driven technologies, including CCIOs and Chief Nurse Information Officers (CNIOs), and newer positions in the C (chief) suite like Chief Analytical Officers, Chief Data Officers and Chief Knowledge Officers. These will have a vital role in managing and setting the strategic direction for digital technology and health informatics in NHS organisations.7

The Goldacre Review also supports the creation of new leadership roles, including a recommendation to ‘create very senior strategic leadership roles for developers, data architects and data scientists.’4 These positions should allow for career progression into senior technical roles as well as management roles. They will need to be supported by clear and flexible training pathways and career trajectories to achieve the specific set of competencies required for digital leadership.

Examples include the following.

- In addition to the STP programme, the National School of Healthcare Science (NSHCS) provides a pathway for clinical bioinformaticians to progress into more senior roles in the NHS through the Higher Specialist Scientist Training (HSST) programme. This 5-year programme supported by a Doctoral level academic award is designed to prepare clinical bioinformaticians to apply to become consultant clinical scientists in the NHS.44

- HEE has established the Digital Health Leadership Programme. The programme is a 12-month fully accredited Postgraduate Diploma in Digital Health Leadership delivered by Imperial College London along with The University of Edinburgh and Health Data Research UK. It is directed at individuals with demonstrable experience (typically three years minimum) of implementing practical digital transformational change within an organisation and/or wider health and care system.45

Expanding these initiatives and providing additional opportunities, career pathways and development programmes for digital leaders may be required to support the creation of new leadership roles.

References

7 Health Education England. Data Driven Healthcare in 2030: Transformation Requirements of the NHS Digital Technology and Health Informatics Workforce. 2021. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/building-our-future-digital-workforce/data-driven-healthcare-2030 Accessed May 24, 2022.

11 Data saves lives: reshaping health and social care with data. Department of health and Social Care. 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/data-saves-lives-reshaping-health-and-social-care-with-data/data-saves-lives-reshaping-health-and-social-care-with-data Accessed June 15,2022.

21 National School of Healthcare Science. Informatics. 2022. https://nshcs.hee.nhs.uk/healthcare-science/healthcare-science-specialisms-explained/informatics/ Accessed May 24, 2022.

22 National School of Healthcare Science. Competing ratios for Scientist Training programme 2021 direct entry posts. 2021. https://nshcs.hee.nhs.uk/publications/competition-ratios-for-scientist-training-programme-direct-entry-posts/2021-html/ Accessed May 24, 2022.

23 Academy for Healthcare Science. Education and Training. 2022 https://www.ahcs.ac.uk/education-training/ Accessed May 24, 2022.

24 London Medical Imaging and AI Centre for Value Based Healthcare. Fellowships. 2022. https://www.aicentre.co.uk/fellowships Accessed May 24, 2022.

25 Royal College of Physicians. Flexible portfolio training. 2022. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/flexible-portfolio-training Accessed May 24, 2022.

8 Health Education England. The Future of Clinical Bioinformaticians in the NHS. 2021. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/building-our-future-digital-workforce/future-clinical-bioinformaticians-nhs Accessed May 24, 2022.

26 Imagine. 2022. http://imagine-talent.com/ Accessed May 24, 2022.

27 Health Education England. Health Innovation Placement (HIP) Pilot. 2022 https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/building-digital-senior-leadership/health-innovation-placement Accessed May 24, 2022.

28 Health Education England. Digital Readiness Education Programme. 2022. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/digital-readiness Accessed May 24, 2022.

29 Health Education England. Regional Informatics Skills Development Networks (ISDNs). 2022. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/supporting-our-digital-experts/regional-informatics-skills-development-networks-isdns Accessed May 24, 2022.

42 NHS Transformation Directorate. Professionalisation. 2022. https://transform.england.nhs.uk/key-tools-and-info/nhsx-analytics-unit/data-and-analytics-partnership-gateway/professionalisation/ Accessed July 19, 2022.

30 Civil Service: Digital, Data and Technology Profession. Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework. 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/digital-data-and-technology-profession-capability-framework Accessed May 24, 2022.

31 NHS. Agenda for change - pay rates. https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/working-health/working-nhs/nhs-pay-and-benefits/agenda-change-pay-rates/agenda-change-pay-rates Accessed May 24, 2022.

32 Faculty of Clinical Informatics. FCI develops a model job description for a Chief Clinical Informatics Officer (CCIO). 2021. https://facultyofclinicalinformatics.org.uk/blog/faculty-of-clinical-informatics-news-1/post/fci-develops-a-model-job-description-for-a-chief-clinical-informatics-officer-ccio-77#:~:text=A%20key%20principle%20of%20the,the%20Office%20of%20the%20CCIO Accessed May 24, 2022.

44 National School of healthcare Science. Higher Specialist Scientist Training programme. 2022. https://nshcs.hee.nhs.uk/programmes/hsst/ Accessed July 19, 2022.

45 Health Education England. Digital Transformation. 2022. https://digital-transformation.hee.nhs.uk/learning-and-development/digital-academy/programmes/digital-health-leadership-programme Accessed July 19, 2022.

Page last reviewed: 20 April 2023

Next review due: 20 April 2024